-It simply has no merit any more

Though a highly speculative topic, it seems to me that we are progressing inevitably toward a breakpoint in modern tertiary education. The past years have seen astronomical rises in the price of education, and the trend is set to continue with analysts from Bloomberg predicting fee hikes in excess of 10% a year for the next five to ten years.

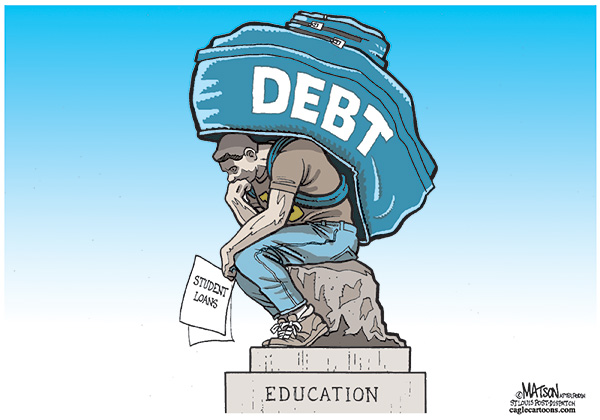

Consistent with the trend education fees have taken, student loans have increased both in numbers and mass. More and more school-leavers are looking to study at a tertiary level, and are taking out student loans to do so.

Some large banks have reported a year on year increase of 6% loan applications , and NSFAS (National Student Financial Aid Scheme) supports around 32% of ALL public University students in some form be it loans, partial loans or bursaries. This is more than double that was given out in 2009.

We are all proponents of greater ‘consumption’ of education, and I am the first to further this agenda, but a major problem arises when we compare these loans with traditional, collaterally-backed loans such as housing mortgages and others. When a financial institution makes a home loan to a customer, they consider many factors- they look at the ability of the customer to repay the interest, the perceived risk of that individual, and importantly, they look at the realizable value of the asset to be bought with the loan. This is crucial, because IF the customer were to default on the loan, they still retain ownership of the real estate asset (or whichever asset is in question), and can sell it on the open market to defray expenses.

COLLATERAL. The most important word in a credit provider’s dictionary. Insurance against defaulting loans.

Education provides no such collateral.

When an 18 year-old takes out a loan to study, he/she can offer no collateral should the deal go bad. What we are finding now is that an 18 year-old’s parents are happy to service the interest charges on the loan throughout the term of study, but when the student graduates three or four years later, he/she faces unemployment, tough times in the corporate world and wages which effectively have less value year on year. Left, right and center we find these graduates defaulting on their loans, unable to make the principle repayments.This is credit gone bad.

Following on from Western trends, 57% of students graduate with debt incurred for their education. The majority of these are still paying back loans in their 30”s. They are in good company: Barack Obama was still paying back his student loans more than a decade later!

The impact of paying back loans later into life, is felt not only by the individual graduate (and his/her family), but also in the economy in general.

Economists in the US argue that student debt is undermining the housing market and dampening the economy. As lenders have become more stringent in their lending, student debt weighs more prominently in determining credit worthiness.

In the United States, 2014 has seen under 35’s hit the lowest level on record for owning a home, and indebtedness has hit a record high, many believing due to student debt.

Although the line has not been definitively drawn between student debt and home ownership, the correlation is not being ignored, and South Africa will undoubtedly be following these trends.

In South Africa, however, there are even further concerns which are connected to historical disparities:

When a regular banking institution is used for debt, it is a for the family of the student to service the loan. Until the graduate can take over the debt, these families are often supporting a first generation university student, whilst themselves struggling financially. Furthermore many do not understand the long term ramifications of servicing (or not servicing) this debt. Although official statistics are not available for delinquency of student loans, and is not believed to be excessive at this point, (due to well regulated and enforced National Credit Act), it would be best if there was transparency on this issue by commercial lending institutions. If the NSFAS lack of debt collection is anything to go by, there may be greater concern required long term.

Further concern is high drop-out rates due to a lack of preparedness of students, for many reasons including students coming from previously disadvantaged schools lack which resources to adequately prepare their school leavers. Thus you are left with a drop out student who does not have the means to service this debt. Obviously the underlying risk of giving student loans, is whether the student eventually graduates and gets full-time employment and pays back the loan.

It is estimated in South Africa that over 25% of students make use of commercial bank institutions to fund their studies, with a further 32% from the NSFAS. General lack of poor financial management to service this debt is of concern, and once again, once has only to look over the Atlantic to see the trend on this.

Is there a bubble? At this point, without full transparency by commercial banking institutions, this cannot be determined, but certainly, looking at statistics from NSFAS debt collection – or lack thereof – and American trends, it is a matter of concern. Our well regulated National Credit Act and Consumer Protection Act, should take care of the commercial institutions in the long run.

With unemployment so high in South Africa, statistics show that tertiary educated unemployment is only sitting at 6%, and further statistics (Centre for Higher Education Transformation), show undeniably that graduates have a higher earning potential.

So to end in the words of Nelson Mandela: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

Leave a reply